The Most Tragic Classic Books (Because Sometimes You Need A Good Cry)

"Those who do not weep, do not see." So warned Victor Hugo, the 19th century Romantic novelist best known for "Les Miserables" and "The Hunchback of Notre Dame." Anyone who's made it to the end of these novels knows he meant it. As the father of French literary sorrow, he gave suffering a voice – not just so we might be entertained by elaborate stories in richly detailed settings, but so we might truly understand the gut wrenching universal truths it can reveal: injustice, compassion, endurance, heartbreak. This is exactly why he makes the list of the most tragic classic books. Sometimes, you simply need a good cry.

But Hugo is far from alone; he is only one in a long lineage of writers who understood literature's capacity to be both a mirror and conduit for the world's most devastating agonies. Tragic fiction grants us access to emotional landscapes we may not have inhabited otherwise, and the following books intimately confront the galling griefs we suppress, and the futile fates we cannot rewrite. And while the tears they provoke can be painful, a good cry can also be beneficial and cathartic — a necessary release. If you need a break from the sunny beach reads of Reese's Book Club, or if you've shelved all the popular romance books in search of something heavier, these reads are your best bet. You'll want to grab the tissues; they'll ask a lot of your heart, but they'll give so much back, too.

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison's "Beloved" deserves to be read with the utmost reverence. Few novels confront its readers quite like it. Inspired by the true story of Margaret Garner, an enslaved captivity and killed her child rather than see her returned to bondage, Morrison exhumes this historical fact into a shattering paragon of classic fiction. Her protagonist, Sethe, is a mother whose love has been so warped by colonial violence that she makes the same unthinkable choice as Garner before her, believing, with devastating conviction, that it was the only one she had.

But "Beloved" does not stop at this horror. The child returns in terrifying ghostly form, haunting Sethe and embodying everything that was cruelly denied from her. Nowhere in the novel is Sethe granted the dignity to exist beyond the scaffolding of her suffering, nor is the reader offered shelter from the relentless beauty and brutality of Morrison's prose. If it's tears you're looking for, this true tragedy will bleed them with an unflinching, elegiac force.

Les Misérables by Victor Hugo

Perhaps it is redundant to say that a novel titled "Les Misérables" — "The Miserable Ones" or "The Wretched Poor" — will leave its readers in tears often, and without mercy. Tragedy works as a plot device and a condition in this 19th century epic: suffering is structural in Victor Hugo's France, and pity is always seemingly slightly out of reach. Set against the convulsions of the French Revolution, Hugo constructs an ethical world in which the smallest gestures of love and kindness resonate reverberate as their own kind of insurrection.

More than a former convict, protagonist Jean Valjean is the author's answer to the tragic hero. He begins as a man punished for stealing bread to help his young nephew survive, and subsequently disgraced by the inhumanity of France's penal system. His attempts at redemption are shadowed by the figure of Javert, a man so loyal to the law that he cannot comprehend justice. But the true tragedy lies not simply in the suffering of one man: it is in the accumulation of forsaken lives orbiting his own. Each character brushes up against love, but it never stays long enough to change their bedevilled fate.

But for all its bleakness, Les Misérables never lets despair have the last laugh. It stubbornly, but no less beautifully, believes love is an act of resistance. Though it will leave you with the satisfying sense that goodness still matters, its sorrow is sweeping and immense, and is sure to leave you in your feelings.

Atonement by Ian McEwan

Briony Tallis is just thirteen when "Atonement," Ian McEwan's modern classic, begins. She is old (and jealous) enough to spin a plausible yarn, but too young to grasp the consequences of telling the wrong one. Her elder sister, Cecilia is home from Cambridge and hovering in a state of post-university aimlessness. Robbie Turner, the housekeeper's son and Cecilia's childhood companion, is on the cusp of real social mobility. That evening, the Tallis family is set to host a gathering, and something is already splintering. And so, the premise of this exquisite period novel unfolds.

A doomed love affair is interrupted before it can take root, unraveling amid the slow decay of a country estate, the complex stratifications of the British class system, a nation inching closer to war, and the suffocating heat of one overripe summer. McEwan's prose is immaculate; he writes with eerie control. Hostility and guilt pool beneath the surface before his narrative fractures them cleanly. Love, separation, sin, and regret are all held in delicate suspension. But by the time McEwan reveals the punishing shape of the story he's truly telling, the damage is already done — and your tissue box will already know it.

The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot

For a duration of her career as a wordsmith, Mary Ann Evans wrote under the name George Eliot. It was a necessary disguise in 1860, when a woman's work was rarely granted the same intellectual or critical seriousness as a man's. "The Mill on the Floss," her third novel, was published that year, and is in many ways her most personal — a story of thwarted female ambition and family failure.

Maggie Tulliver is one of Eliot's most vivid creations, and remains a beloved heroine today. She is restless, bright, unruly, and far too clever and emotionally alive for the small-minded provincial world she was born into. Her brother, Tom, is her moral opposite: proud and rigid in his moralism, and just as emotionally withholding. Their relationship is formative, yet ruinous, and it drives the novel's emotional arc in the most tragic way. Maggie needs to be free and loved for who she is; Tom only knows how to love her when she behaves like someone else.

As Eliot approached the ending of this requiem of lost innocence, she cried daily. Reader, prepare yourself for this cumulative ache. This is not a novel that simply ends in tears, It will drag you, body and soul, into the flood with them.

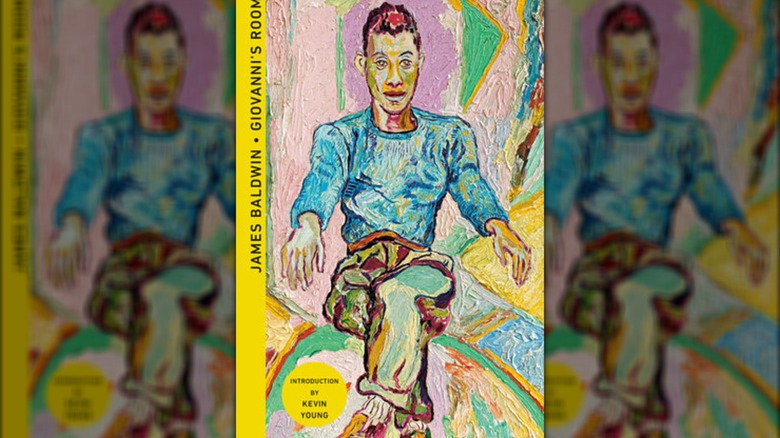

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin

James Baldwin wrote with such precision and heat that even his most positive speeches can bring you to tears. So, when he turns from the collective language of hope to the intimate territory of injustice, shame, longing, and self-erasure — as he does so deftly in "Giovanni's Room" — the waterworks are guaranteed.

The novel centres on David, an American adrift in 1950s Paris, living in borrowed apartments and borrowed identities, torn as he is between his socially acceptable engagement to a woman and his all-consuming love for Giovanni, an Italian bartender — a love he has been taught cannot survive daylight. The tragedy here is quite claustrophobic: a slow suffocation by societal expectation, shame mistaken for virtue, the psychic cost of compartmentalizing the self, and the violence of denial.

Baldwin renders this internal collapse with devastating elegance. So much so, it was also chosen as one of Natalie Portman's book club picks. The prose is sparse, but the heartbreak is not. The grief will seeps in gradually, and will leave you with a lump in your throat.

How we chose the books

All the titles included here fall under the banner of classic fiction – canonized works that continue to speak across decades and cultures with literary force. But these books weren't simply chosen for their narrative longevity, but also for the way they move us, and their ability to draw out sorrow. Without resorting to mawkish sentimentality, they ache with nuance and present emotional ruptures through character, voice, and form.

The selection spans different continents, periods, and perspectives, since no one geography or timescale owns the territory of grief. But they continue to speak powerfully to readers, and we hope their themes and players will appeal to our Women readership.